“The big idea is their idea.”

-Karen Wilkinson

As a designer and constructionist educator, I create environments that support learner-driven creativity. In the course of designing digital and physical learning through play activities and experiences used in LEGO House and other informal learning spaces around the world, I’ve curated and created a small collection of guiding principles. Many of these were inspired by great partners I’ve been lucky to work with at MIT Media Lab and the Exploratorium.

These principles are especially useful when thinking about the design of open-ended play or “Tinkering” activities, which are different from other types of playful learning like games. Tinkering activities are designed to invite the learner to decide what to create or explore and how to create it. To see an example of an open-ended playful learning experience, take a look at SkyParade.

Low floor, High ceiling

Seymour Papert, author of Mindstorms and founder of Constructionist Learning Theory

A ‘Low floor ’ means that it is easy for the learner to orient themselves and get started with the playful activity. The quintessential low-floor high ceiling play material is the LEGO brick: It takes only a moment to understand how it works, and once you have that understanding you can build everything from a simple duck to a model of the Eiffel Tower. Tools and interfaces - digital or otherwise - should be designed with a similar aspiration: they must be easy to use and understand, so that a wide range of learners with different competences can easily get started (low floor). But it should also be possible to build and explore complex ideas (high ceiling).

A tinkering activity or play material with a “low floor and high ceiling” will be interesting to a wide range of people in terms of age and experience, because each of them can engage with it at their own level.

What it looks like:

When a learner engages with something that’s confusing or overly complex – for example, a computer interface that’s difficult to immediately understand - they will show it. It often looks like reluctance to engage, with perhaps a few ineffectual stabs at trying something, followed by frowns, followed by a retreat to more familiar ground. Designers must watch for encounters with their activities and tools that look like this, and try to understand which aspects of the interface were confusing and need to be simplified and / or clarified.

“It’s important to be open-ended, but it’s ok to be closed started."

-Jay Silver, co-inventor of MaKey MaKey

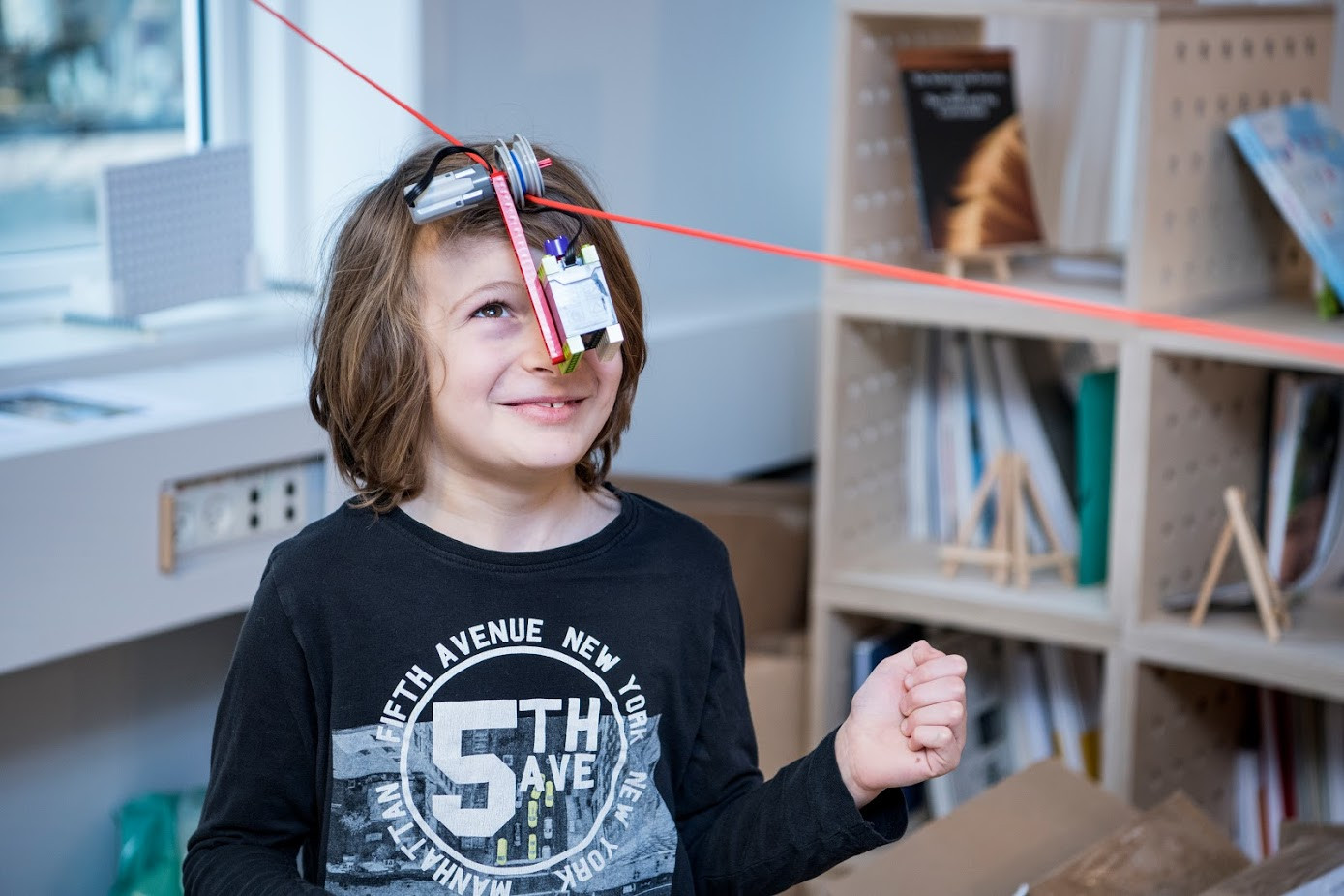

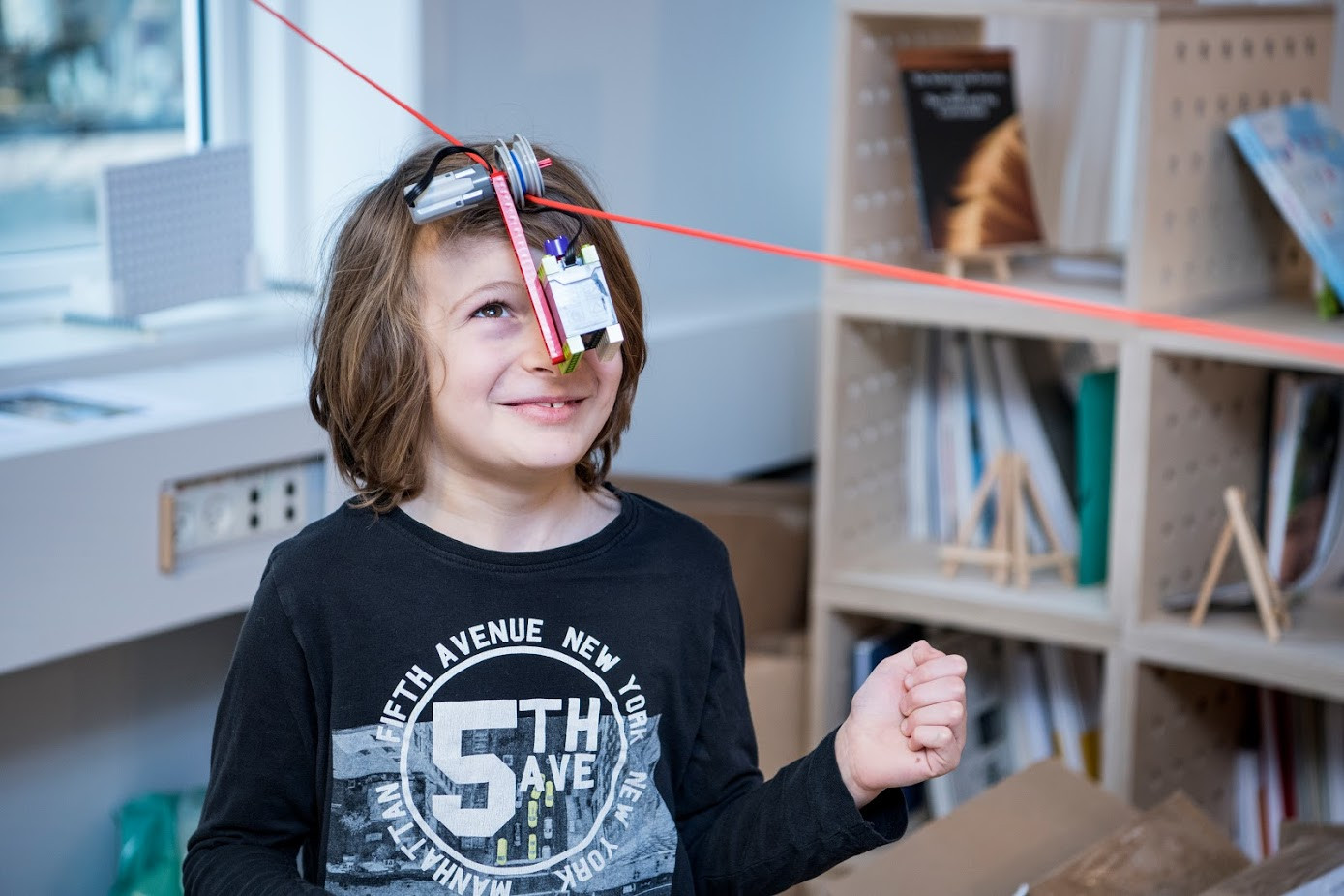

When designing activities that introduce children to new tools for creative self-expression, it’s ok to start out with very limited tasks and constraints (i.e. insert tab A into slot B.) But as the activity progresses, the design should encourage more and more freedom to choose what to make and how to make it, allowing the learner to take their project in their own unique direction.

Asking children to solve a problem defined by the designers of the experience is ok. But inviting them to define their own problems and solutions in a space with lots of possibilities leads to deeper engagement and learning.

What it looks like:

At the start of the activity, look for signs of what authors and artists call “white piece of paper” syndrome. This is evident when a creator doesn’t know how to begin creating something or otherwise engaging with the activity. When this happens, try constraining their first task, so there’s less to think about when they are just getting started. Once the child has established some confidence about working with the tools and materials, gradually invite them to set their own direction.

Respect the learner’s Agency

Learners of all ages know best where their interests and abilities lie. It’s crucial that they have the freedom to choose what to engage with and how to engage with it. It can be a valuable experience for a child or adult to achieve a goal that the designers of an activity have set for them. It is a much more valuable experience when they set their own goals. From a design point of view this makes open-ended playful learning activities much more challenging than providing a simple “gamified” end goal. But it makes for a much more meaningful, valuable, and empowering learning experience.

This doesn’t mean that designers can’t place constraints or set frames on an activity. It simply means that within those constraints the child should have freedom to explore and develop their own ideas.

What it looks like:

The best general evidence of room for agency is diversity of outcomes -- when each child uses an activity to create something unique based on their interests and skills. Another sign of agency is when a learner creates something that breaks the normal frame of an activity. If you’ve asked them to create buildings in a city and they create buildings that turn into spaceships and fly, they’ve taken your constraint and creatively reinterpreted it (and that’s a good thing). Rule breaking, provided it doesn’t ruin the experience for others, is a sign of a strong sense of agency.

Look for Engagement and Fun

Playful learning is both fun and engaging. Sometimes it looks like intense focus while designing and building, and sometimes it looks like laughter and joking while playing with friends. Both show that the participants care about and are engaged with the experience they are having.

A powerful open-ended play experience should strive to engage children in what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called “Flow,” which he defined as “a state of concentration or complete absorption with the activity at hand and the situation.”

What it looks like:

Engagement in children looks like focus and fun, with movements between different aspects of the experience. Apathy looks like a retreat to the perimeter of the activity without returning for another try, or otherwise being reluctant to or uninterested in diving in. Engaged kids will often not want to leave when it’s time to go, make loud noises of frustration or excitement, and generally show that they care about what is happening.

Design for Iteration and Feedback

Designing for open-ended play is a meta process, because it puts us in the role of designing for the learner as a designer. All design depends on iteration and feedback. Playful learning activities should allow the learner to work on their creation, get feedback (in terms of what it does or how it looks), and continue to iterate or polish what they’ve made based on that feedback.

Feedback can be loosely classified into two categories:

objective feedback comes from observations by the learner i.e. ‘My car crashes at the bottom of the ramp.’

subjective feedback comes from aesthetic judgment – their own or someone else’s. For example: “I like the front of my spacecraft but the tail doesn’t look quite right,” or “The facilitator says she likes my build, but she thinks the ears could use some improvement.”

Iteration based on feedback is crucial to the success of a creative learning experience. The structure of school tends to discourage iteration because students usually submit a writing assignment once and then receive a grade. That’s an iteration count of one (or maybe two if they made a rough draft.) A rich creative play experience should strive for iteration counts in the range of 10-100 per hour.

What it looks like:

Iteration is a process of refinement, thus the first attempts at something are often crude or rough. In an experience building vehicles that drive down ramps, most iteration is in response to objective feedback: The child tests the car on the ramp, observes what happens, and then makes changes to their design. For an experience that depends on subjective feedback, iteration looks like brief pauses while building, during which the learner looks carefully at their creation, and then continues refining it.

Design for Reflection

Reflection allows the learner to integrate their experiences into their mental model of the world. As this model becomes more refined and accurate, it begins to shed light on the relationships between things, which leads to new insights and new ideas.

Reflection can occur within the feedback iteration loop or after the play experience is over. Designers should include time for reflection in the experience and try to stimulate it afterwards. Show and tell is an invitation for group reflection.

What it looks like:

Solitary reflection is difficult to see because it’s an internal mental process. Some people reflect while staring at things with vacant expressions. Some people scratch their heads or purse their lips. When children discuss their experiences and use metaphors to connect it to other ideas, it’s likely they’ve been doing some reflection.

Conclusion

Learning and play are deeply complex. There are many more things to be aware of when designing and facilitating creative learning experiences. These guidelines can help orient one to areas that are especially important to focus on. But ultimately the only way to make and maintain great playful learning experiences is to set up an ongoing process of creative iteration and reflection. The educators and children of Reggio Emilia have pioneered the use of Documentation as the core of a reflective process that, to me, seems like the most powerful and important educational practice I’ve ever encountered. I’ll write more on that in the future.